Statistical whitening with 1D projections

Geometric intuition for our recent paper on statistical whitening using overcomplete bases.

A short Tweet thread about this paper can be found here.

A very old problem in statistics and signal processing is to statistically whiten a signal, i.e. to linearly transform a signal with covariance \({\bf C}\) to one with identity covariance. The most common approach to do this to find the principal components of the signal (the eigenvectors of \({\bf C}\)), then scale the signal according to how much the it varies along each principal axis. The downside of this approach is that if the inputs change, then the principal axes need to be recomputed.

In our recent preprint (https://arxiv.org/abs/2301.11955), we introduce a completely different and novel approach to statistical whitening. We do away with finding principal components altogether, and instead develop a framework for whitening with a fixed frame (i.e. an overcomplete basis) using concepts borrowed from frame theory of linear algebra, and tomography, the science of reconstructing signals from projections.

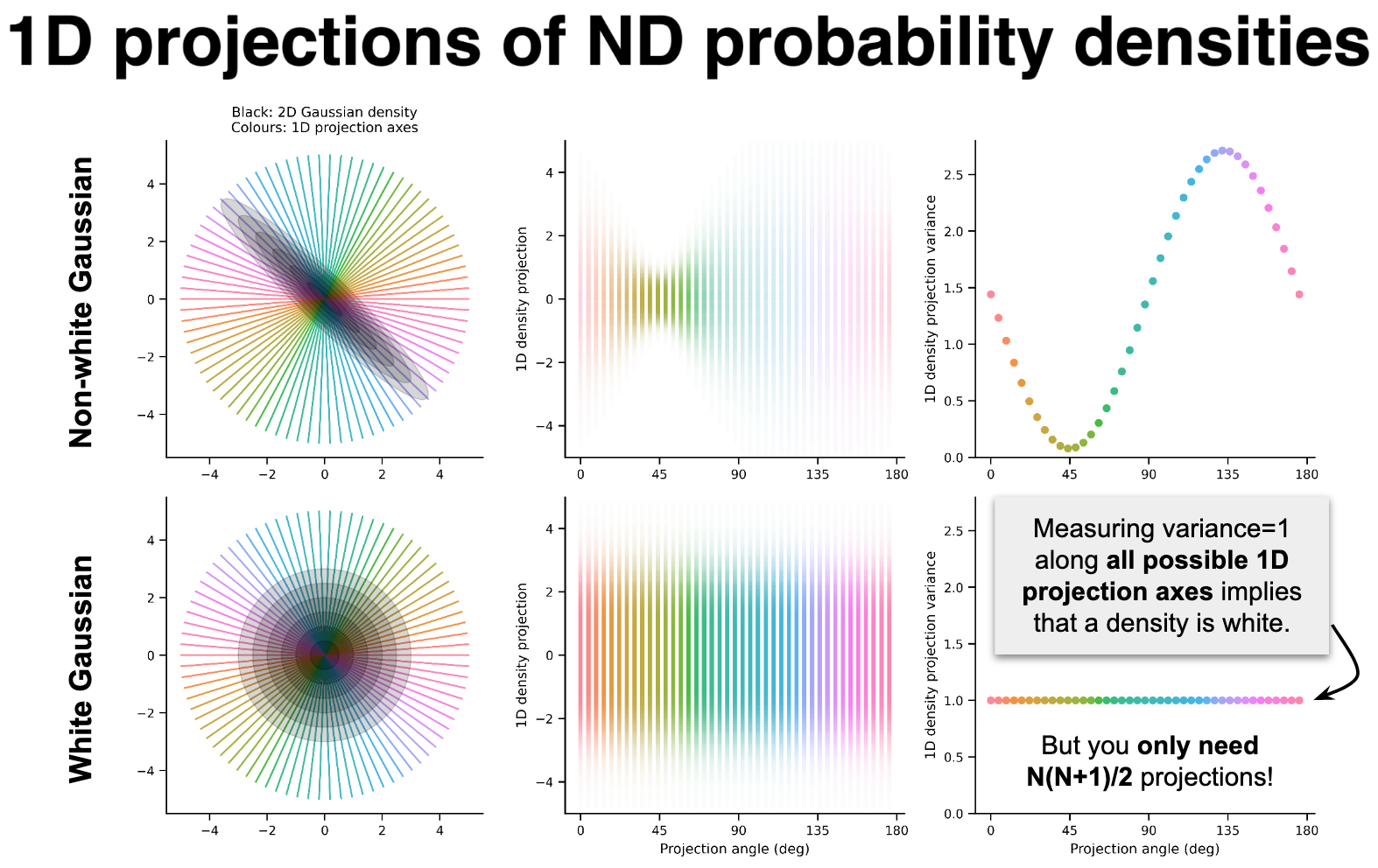

The figure above shows the geometric concepts behind our approach. It’s useful to know that we can geometrically represent densities with covariance matrices \({\bf C}\) as ellipsoids in \(N\)-dimensional space (top left panel, shaded black). Old work in tomography has shown that ellipsoids can be represented (reconstructed) from a series of 1D projections. The 1D projected densities are plotted as vertical lines in the middle panel, with colours corresponding to the axes along which the original density was projected, and colour saturation denoting probability at a given point. It turns out that if the density is Gaussian, then \(N(N+1)/2\) projections along unique axes are necessary and sufficient to represent the original density. This number of required projections is the number of independent parameters in a covariance matrix. Importantly, the set of 1D projection axes can exclude the principal components of the original density, and is overcomplete, i.e. linearly dependent, since there are more than \(N\) projections.

Unlike conventional tomographic approaches, the main goal of our study isn’t to reconstruct the ellipsoid, but rather to use the information derived from its projections to whiten the original signal. The top right plot shows each 1D marginal density’s variance; notice how the variance of the 1D projections is proportional to the length of the corresponding 1D slice, and that for this non-white joint density, the variances are quite variable. Meanwhile, for a whitened signal (bottom row), all projected variances equal 1! This geometric intuition involving 1D projections of Gaussian densities forms the foundation of our framework.

In the paper we show: 1) how to operationalize these geometric ideas into an optimization objective function to learn a statistical whitening transform; and 2) how to derive a recurrent neural network (RNN) that iteratively optimizes this objective, and converges to a steady-state solution where the outputs of the network are statistically white.

Mechanistically, this RNN adaptively whitens a signal by scaling it according to its marginal variance along a fixed, overcomplete set of projection axes, without ever learning the eigenvectors of the inputs. This is an attractive solution because constantly (re)learning eigenvectors with dynamically changing inputs may pose stability issues in a network. From a theoretical neuroscience perspective, our findings are particularly exciting because they generalize well-established ideas of single-neuron adaptive efficient coding via gain control to the level of a neural population.